Article Content

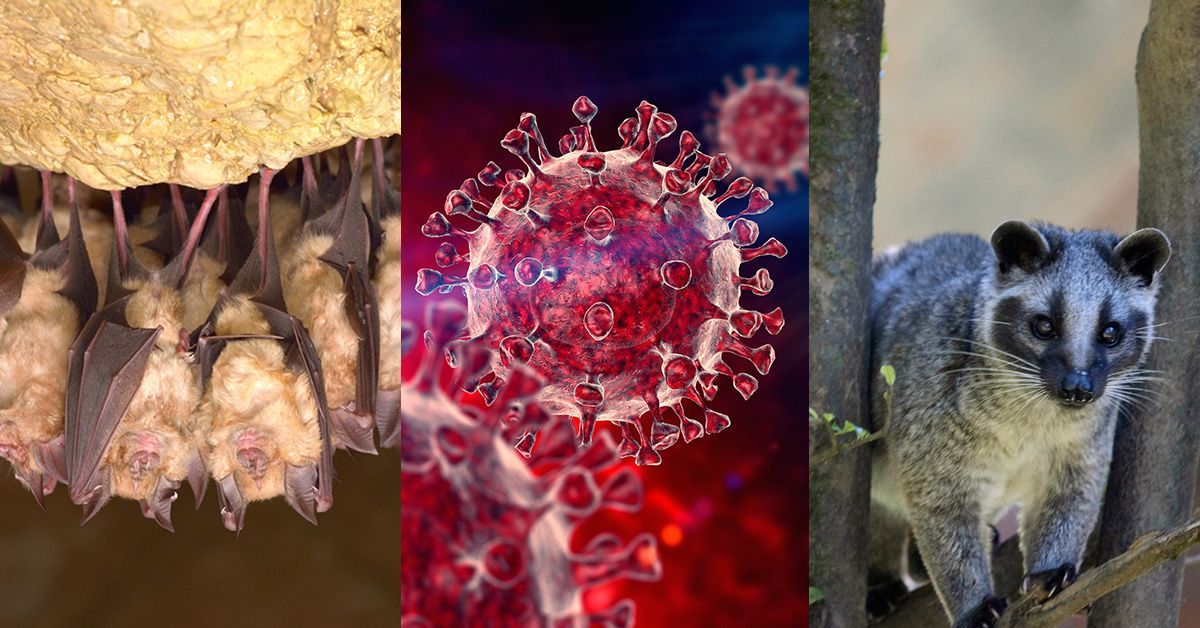

The ancestor of the virus that causes COVID-19 left its point of origin in Western China or Northern Laos just several years before the disease first emerged in humans up to 2,700 kilometers away in Central China, according to a new study by University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers and their colleagues. That’s not enough time for the evolving virus to have been carried there via the natural dispersal of its primary host, the horseshoe bat. This has led the researchers to conclude that it instead hitched a ride there with other animals via the wildlife trade, consistent with what happened during the SARS outbreak in 2002. The study was published in Cell on May 7, 2025.

Horseshoe bats are the main hosts of sarbecoviruses. These viruses don’t harm the bats, but are thought to have made the leap to humans through “zoonotic spillover” events. Sarbecoviruses gave rise to severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-1, the strain that caused the SARS pandemic of 2002-2004, and SARS-CoV-2, the strain that resulted in the COVID-19 pandemic. How they got to the places where these events occurred and whether animals besides bats were involved has been a matter of ongoing debate, however.

To clarify these questions, the researchers analyzed the family tree of both viral strains using genome sequence data available online, mapping their evolutionary history across Asia before they emerged in humans. However, the picture was blurred by the fact that these RNA viruses undergo a large amount of recombination inside their bat hosts, exchanging genetic material.

“When two different viruses infect the same bat, sometimes what comes out of that bat is an amalgam of different pieces of both viruses,” said co-senior author Joel Wertheim, Ph.D., a professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health. “Recombination complicates our understanding of the evolution of these viruses because it results in different parts of the genome having different evolutionary histories.”

The researchers avoided that problem by identifying all of the non-recombining regions of the viral genomes and using those to recreate the evolutionary history of the viruses instead.

The study found that sarbecoviruses related to SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 have circulated around Western China and Southeast Asia for millennia. During this time, they moved around the landscape at similar rates as their horseshoe bat hosts.

“Horseshoe bats have an estimated foraging area of around 2-3 km and a dispersal capacity similar to the diffusion velocity we estimated for the sarbecoviruses related to SARS-CoV-2,” said co-senior author Simon Dellicour, Ph.D., head of the Spatial Epidemiology Lab at Université Libre de Bruxelles and visiting professor at KU Leuven.

In contrast, the analysis also revealed that the most recent sarbecovirus ancestors of both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 left their points of origin less than 10 years before they were first reported to infect humans — more than a thousand kilometers away.

“We show that the original SARS-CoV-1 was circulating in Western China — just one to two years before the emergence of SARS in Guangdong Province, South Central China, and SARS-CoV-2 in Western China or Northern Laos — just five to seven years before the emergence of COVID-19 in Wuhan,” said Jonathan E. Pekar, Ph.D., a 2023 graduate of the Bioinformatics and Systems Biology program at UC San Diego School of Medicine, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Edinburgh.

The researchers calculated that given the distances that SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 would have had to cover so quickly, it is highly improbable that they could have been carried there via bat dispersal. Much more likely: they were transported there accidentally by wild animal traders via intermediate hosts.